The Strathearn Canal that never was

If we could travel back in time to 1800, we would see a very different Crieff and Strathearn. In the days before cars and trains and tourists, people generally didn’t travel very far from home. Crieff was a small, but growing town with many thatched cottages and a population of 2,071 (in 1792). Commissioner Street had been recently created and a number of new houses built. However, according to the Old Statistical Account, many of these houses ‘would lie waste’ were it not for the town’s location on one of the principal roads into the Highlands. Because of this, Crieff was one of the first places reached by people cleared off the land to make way for sheep-farms and who had no other employment and nowhere else to go.

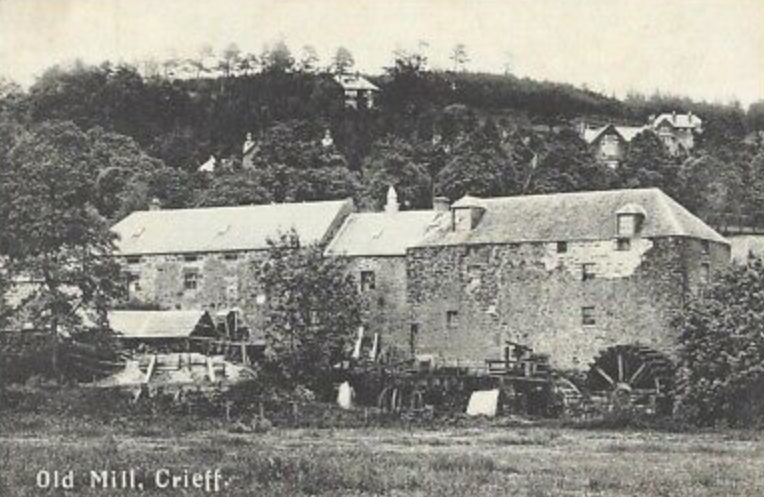

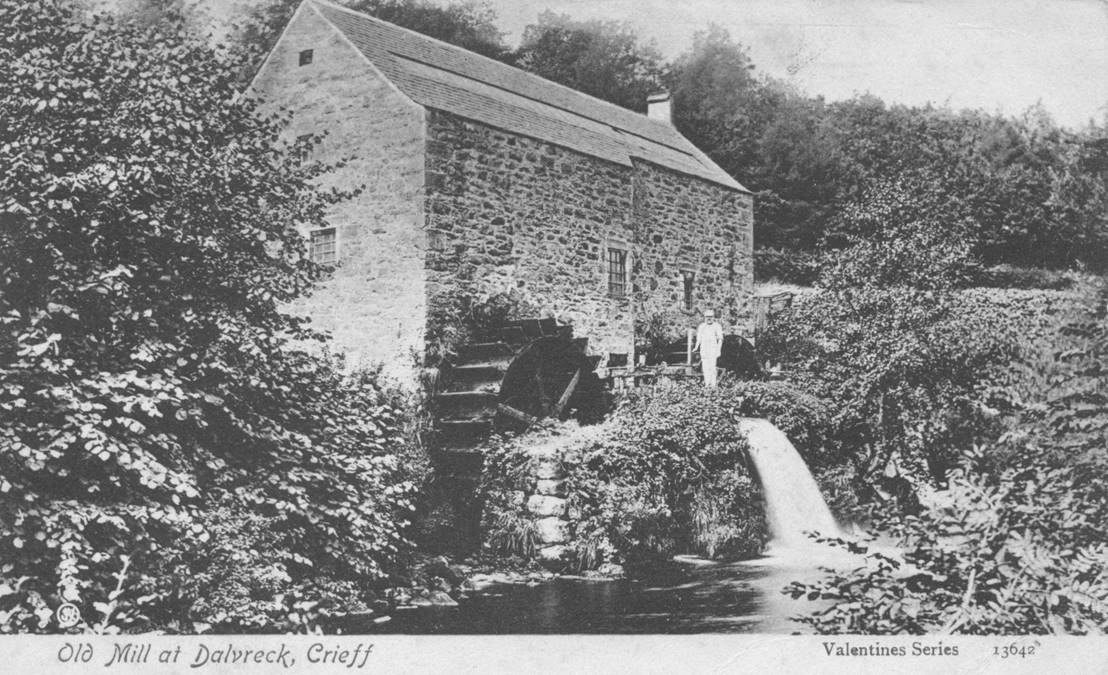

The huge annual Crieff Tryst had moved to Stenhousemuir and became the Falkirk Tryst in 1785 and Crieff, with much of Strathearn, became reliant on agriculture and weaving and there were also mills in the area which provided employment. There were corn and barley mills, lint mills (these prepared the fibres of flax plants for spinning into linen), an oil mill which pressed lintseed to extract oil, a paper mill, and two mills for carding and spinning cotton (the carding mill prepared wool for spinning by aligning the fibres).

{Milnab Mills are Crieff’s oldest mills and consisted of grain mills and waulk mills, both worked off the lade which now runs through MacRosty Park. (Culture Perth & Kinross Collection)}

These mills employed a considerable number of adults and children. A tambouring manufacture recently established, employed 30 girls from 8-12 years of age to do embroidery. There were also two distilleries, a brewery and two tanneries. Despite this, many local people worked in their own homes as weavers – some as a full-time job, while many farmers used their gains from weaving to pay their rents. The Old Statistical Account states that, ‘Until recently the weavers worked mainly in linen and course woollens’, but some have moved ‘to work on a coarse linen and some on weaving cotton cloth. This cloth is all sent to Glasgow where it is whitened and printed.’(Unfortunately much of this material was likely bound for the slave plantations).

{Dalvreck Mill was built in 1831 and stood on the banks of the River Turret. (Culture Perth & Kinross Collection) + Handloom Weaver at work. (Cotton Town project)}

From this it can be seen that Crieff was a relatively prosperous place and was providing employment and services for people not only in the town, but also for those who lived and worked in the surrounding area and further afield.

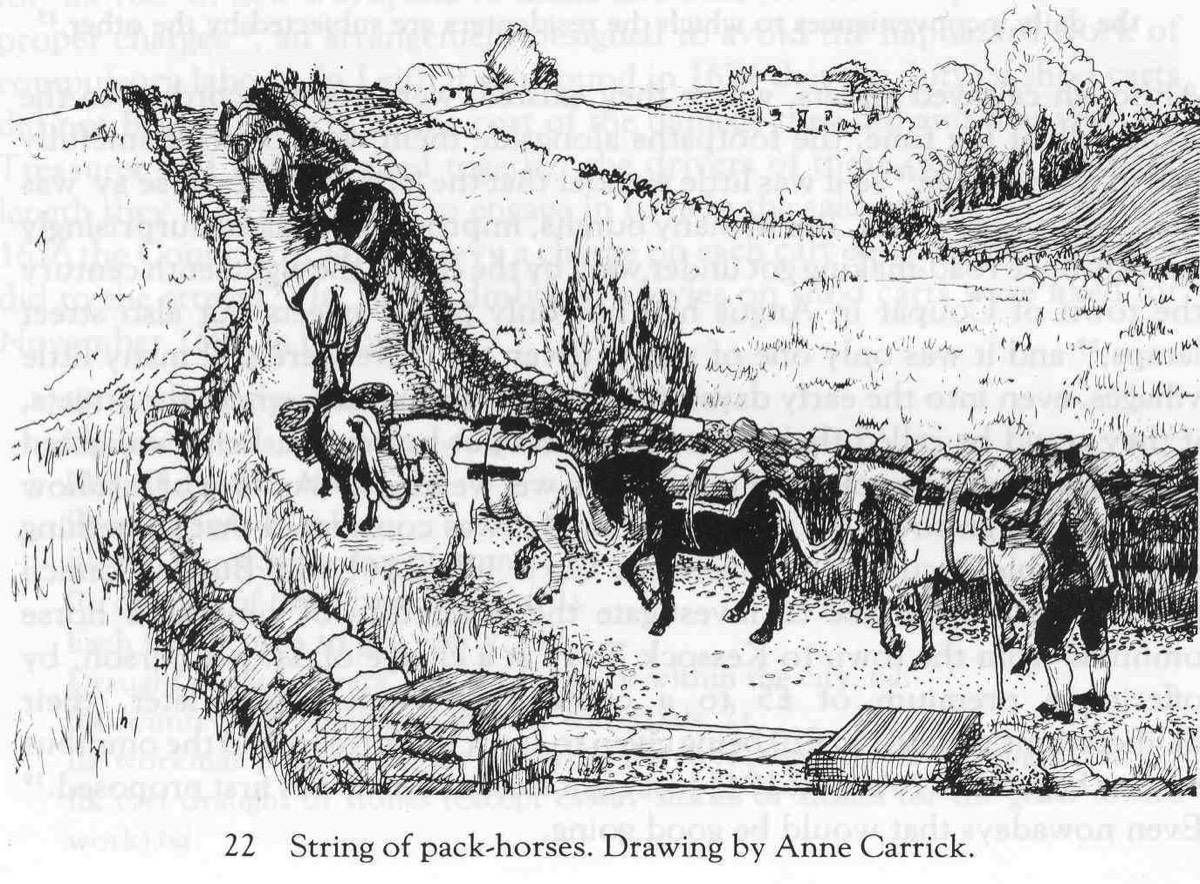

To serve these weavers, mills and farms there were around 29 carters who travelled to and from the larger cities. The Old Statistical Account records that, ‘the exports are coarse-linen, pack-sheeting..; tanned leather; paper; lintseed oil; linen and cotton yarn; and some cotton cloth…. The imports are black cattle and sheep for slaughter; butter and cheese; whisky, porter, and wine; lintseed; lint, wool and raw cotton; linen and woollen yarn; wood and iron….For conveying these goods and manufactures, 2 carts go regularly once a fortnight to Edinburgh; 2 carts or more once a fortnight to Glasgow; 4 carts twice a week to Perth; and 2 or 3 carts twice a week to Stirling.’ On top of this there were carts driven to the nearest coal mines at Bannockburn and Dollar. (In 1793 coal was 2-3x more expensive in Crieff and Comrie compared to Perth, although for a while apparently still cheaper than peat or wood.)

To serve these weavers, mills and farms there were around 29 carters who travelled to and from the larger cities. The Old Statistical Account records that, ‘the exports are coarse-linen, pack-sheeting..; tanned leather; paper; lintseed oil; linen and cotton yarn; and some cotton cloth…. The imports are black cattle and sheep for slaughter; butter and cheese; whisky, porter, and wine; lintseed; lint, wool and raw cotton; linen and woollen yarn; wood and iron….For conveying these goods and manufactures, 2 carts go regularly once a fortnight to Edinburgh; 2 carts or more once a fortnight to Glasgow; 4 carts twice a week to Perth; and 2 or 3 carts twice a week to Stirling.’ On top of this there were carts driven to the nearest coal mines at Bannockburn and Dollar. (In 1793 coal was 2-3x more expensive in Crieff and Comrie compared to Perth, although for a while apparently still cheaper than peat or wood.)

All of this carting was being driven over very poor quality roads and so journeys took a long time, were very inefficient and therefore expensive.

To improve this, the government passed Bills for roads planned many years before. In May 1793 there was - 'An Act for ….making and repairing the Road from Crieff towards Stirling…’; and in 1796 'An Act for ….making and repairing the Road from Perth to Crieff …’(now the A85). These Bills were originally passed in 1767, but road-building was halted on the death of Major William Caulfield that year. Although these Acts resulted in better roads, the size of carts restricted the amount of goods which could be transported, and this included bulky items such as coal, fertiliser and lime - and it also involved paying tolls! Lime was quarried at the western end of Loch Earn, but then transported to the eastern end where it could be burnt to form quicklime or slaked lime. This was applied to the land to raise its pH levels and make it more fertile. In 1823, John Brown in his ‘Picture of Strathearn’, mentions, ‘That inexhaustible source of fertility and wealth to Strathearn, the Lime Quarry, …. is the property of Lord Breadalbane, and is at present under lease to Messrs. John McCrorie and Company. They give daily employment to the company of a large boat (which holds 60-70 bolls of limestone), built for the purpose of conveying the stones to the east end of the loch; from which station, those who need must drive them on carts, at times to the distance of 20 miles.’ (The legacy of this industry could be seen as the A85 alongside Loch Earn – could this have been the old towpath where horses once towed along barges of limestone and the reason why the road is so close to the loch in many places?) Much of the lime was required further down Strathearn where it was especially useful for improving reclaimed land. Unfortunately the carting was expensive and if the lime had to be driven over 10 miles, then the carting could end up costing more than the lime.

To improve this, the government passed Bills for roads planned many years before. In May 1793 there was - 'An Act for ….making and repairing the Road from Crieff towards Stirling…’; and in 1796 'An Act for ….making and repairing the Road from Perth to Crieff …’(now the A85). These Bills were originally passed in 1767, but road-building was halted on the death of Major William Caulfield that year. Although these Acts resulted in better roads, the size of carts restricted the amount of goods which could be transported, and this included bulky items such as coal, fertiliser and lime - and it also involved paying tolls! Lime was quarried at the western end of Loch Earn, but then transported to the eastern end where it could be burnt to form quicklime or slaked lime. This was applied to the land to raise its pH levels and make it more fertile. In 1823, John Brown in his ‘Picture of Strathearn’, mentions, ‘That inexhaustible source of fertility and wealth to Strathearn, the Lime Quarry, …. is the property of Lord Breadalbane, and is at present under lease to Messrs. John McCrorie and Company. They give daily employment to the company of a large boat (which holds 60-70 bolls of limestone), built for the purpose of conveying the stones to the east end of the loch; from which station, those who need must drive them on carts, at times to the distance of 20 miles.’ (The legacy of this industry could be seen as the A85 alongside Loch Earn – could this have been the old towpath where horses once towed along barges of limestone and the reason why the road is so close to the loch in many places?) Much of the lime was required further down Strathearn where it was especially useful for improving reclaimed land. Unfortunately the carting was expensive and if the lime had to be driven over 10 miles, then the carting could end up costing more than the lime.

{Loch Earn at St.Fillans where the lime boats would have arrived from further up the loch. (David Ferguson)}{One of the Limekilns at st.Fillans. (David Ferguson)}{Limekiln Manager’s House at St.Fillans and now incorporated into the Four Seasons Hotel. (David Ferguson)}

Across central Scotland similar transport difficulties had been identified and the main solution was seen to be building canals, as it was reckoned one horse could convey 100x the quantity by water than by land. During the late 1700’s a number of canals were proposed, and in many cases construction started, including the Forth & Clyde, Crinan, Edinburgh & Glasgow Union, Caledonian, Campbeltown to Machrihanish, and an extension to the Monkland. All of these were seen as being the desired mode of transport to move bulky goods quickly and efficiently. Landowners and merchants in Strathearn were not behind as around 1770 James Watt, the brains behind the steam engine, reviewed the land between Crieff and the Tay for a canal, where he suggested it should follow the course of the river and run from Earnmouth rather than Perth harbour, but unfortunately the idea foundered.

{James Watt Scottish inventor and Engineer who did an overview of the land between the River Tay and Crieff for its suitability for a canal. (Online)}

However, the idea didn’t die as in June 1793 a proposal was made by James Drummond Esq.,Comrie, when he published

‘Remarks concerning the formation of a navigable canal, betwixt Perth and Loch Ern. It is proposed to open a communication , by water, through the inland parts of Perthshire, for a tract of 40 miles, commencing at the town of Perth and firth of Tay, and extending westward by Crieff and Comrie to Lochern. A canal of about four feet deep and eight feet broad, is supposed sufficient for this purpose, with convenient passing places upon the sides. The course of it, in general, could be directed through a level country; insomuch, that for a space of 12 or 14 miles no lock would be necessary. Still the expense of such an undertaking must be considerable, and, might amount to about 30,000librum (pounds).’

An online site suggests that could equate to around £243m in 2020. In addition to the canal there was an intention

“ that the canal should be joined at Comrie by a turnpike road, leading from Stirling , by Dumblane and Glenlichorn, and through Glenlednick, to Loch Tay side; so that, in this manner, a complete communication would be opened through a country of some hundred miles of extent , containing upwards of 100,000 people.“

(Although the canal was not built, the Glenlichorn road was constructed in around 1810.)

No doubt the huge cost deterred investors and 5 years later James seems to have suggested an abbreviated version of his plan

‘..that a canal from Perth to Crieff, a distance of less than 20 miles, almost upon a dead level, which might be accomplished at an expense of about 10,000l. (around £81m in 2020)’

Time passed and another survey for a canal was commissioned by authorities in Perth in 1807. John Rennie, renowned canal engineer, carried out a survey and produced a report, which seems to have gone to Parliament

‘A Bill for making and maintaining a navigable canal from the River Tay, near to and on the south side of the town of Perth, to Loch Earn in the County of Perth.’

The Preamble continues, ‘it would not only facilitate and render less expensive the conveyance of goods, wares, and merchandise between the towns of Dundee, Perth and Crieff and other places, and particularly the Highlands, but would also promote the improvement and cultivation of the adjacent country by conveyance of manure, and would be otherwise of much public advantage and utility; but the same cannot be effected without aid and authority of Parliament.’

‘Remarks concerning the formation of a navigable canal, betwixt Perth and Loch Ern. It is proposed to open a communication , by water, through the inland parts of Perthshire, for a tract of 40 miles, commencing at the town of Perth and firth of Tay, and extending westward by Crieff and Comrie to Lochern. A canal of about four feet deep and eight feet broad, is supposed sufficient for this purpose, with convenient passing places upon the sides. The course of it, in general, could be directed through a level country; insomuch, that for a space of 12 or 14 miles no lock would be necessary. Still the expense of such an undertaking must be considerable, and, might amount to about 30,000librum (pounds).’

An online site suggests that could equate to around £243m in 2020. In addition to the canal there was an intention

“ that the canal should be joined at Comrie by a turnpike road, leading from Stirling , by Dumblane and Glenlichorn, and through Glenlednick, to Loch Tay side; so that, in this manner, a complete communication would be opened through a country of some hundred miles of extent , containing upwards of 100,000 people.“

(Although the canal was not built, the Glenlichorn road was constructed in around 1810.)

No doubt the huge cost deterred investors and 5 years later James seems to have suggested an abbreviated version of his plan

‘..that a canal from Perth to Crieff, a distance of less than 20 miles, almost upon a dead level, which might be accomplished at an expense of about 10,000l. (around £81m in 2020)’

Time passed and another survey for a canal was commissioned by authorities in Perth in 1807. John Rennie, renowned canal engineer, carried out a survey and produced a report, which seems to have gone to Parliament

‘A Bill for making and maintaining a navigable canal from the River Tay, near to and on the south side of the town of Perth, to Loch Earn in the County of Perth.’

The Preamble continues, ‘it would not only facilitate and render less expensive the conveyance of goods, wares, and merchandise between the towns of Dundee, Perth and Crieff and other places, and particularly the Highlands, but would also promote the improvement and cultivation of the adjacent country by conveyance of manure, and would be otherwise of much public advantage and utility; but the same cannot be effected without aid and authority of Parliament.’

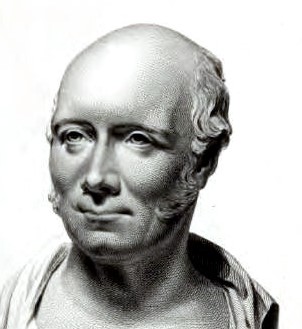

{John Rennie, Engineer, who surveyed for a canal between Perth and Loch Earn in 1807. (Online)}

The project was not to cost more than £150,000 (£840m in 2020 – Edinburgh Tram Project completed in 2014 cost £776m+) and the Company was to be called ‘The Tay and Loch Earn Canal Company’. Shares of £50 would be issued amounting to £150,000 in total. It went on to say that if the money raised was insufficient, more shares could be issued to raise a further £75,000 (£420m in 2020).

Again nothing seems to have come from this as around 20 years later Robert Stevenson, father of the engineering family more associated with lighthouse building, was commissioned to compile a report on the possibility of a canal or a railway along Strathearn; ‘A Memorial regarding the Propriety of Opening the Great Valles of Strathmore and Strathearn by means of a Railway or Canal’ was published on 1st July 1820.

Again nothing seems to have come from this as around 20 years later Robert Stevenson, father of the engineering family more associated with lighthouse building, was commissioned to compile a report on the possibility of a canal or a railway along Strathearn; ‘A Memorial regarding the Propriety of Opening the Great Valles of Strathmore and Strathearn by means of a Railway or Canal’ was published on 1st July 1820.

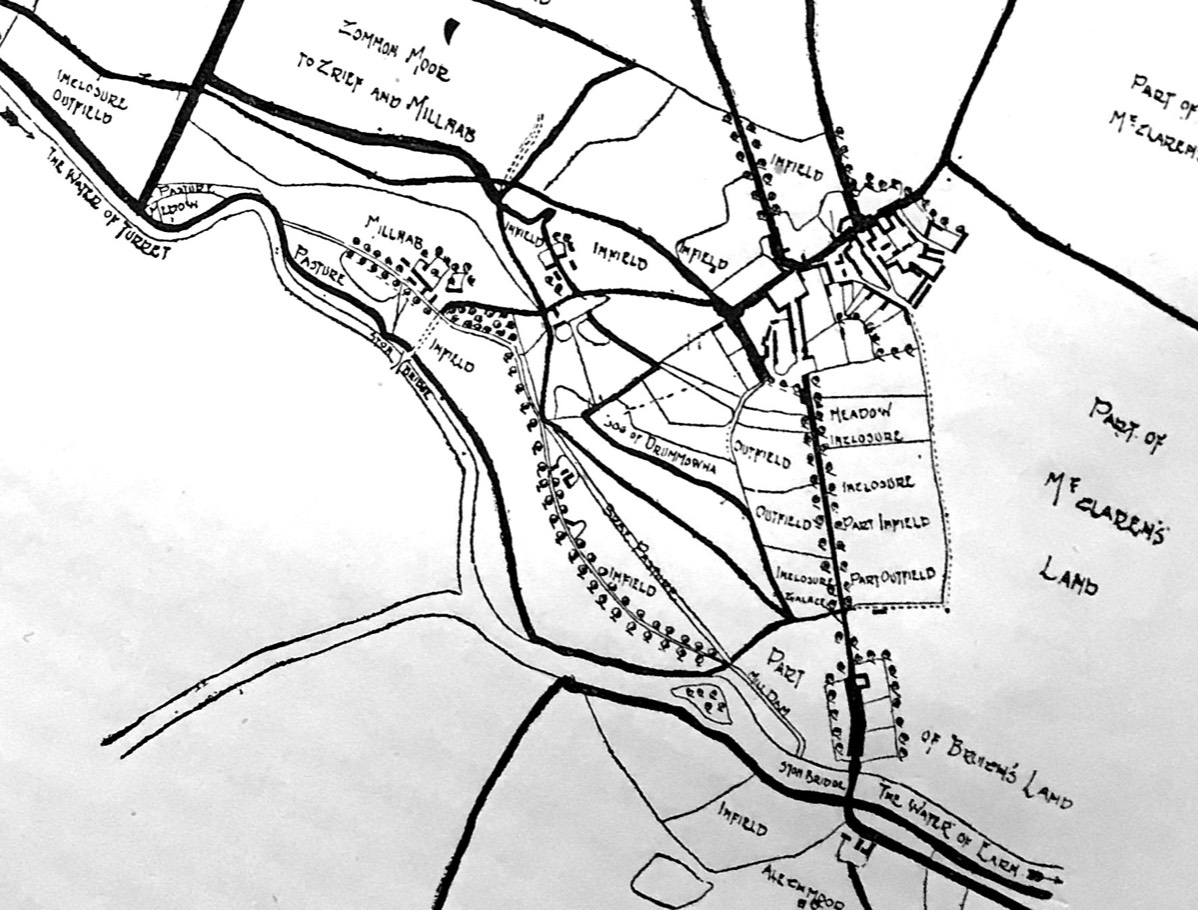

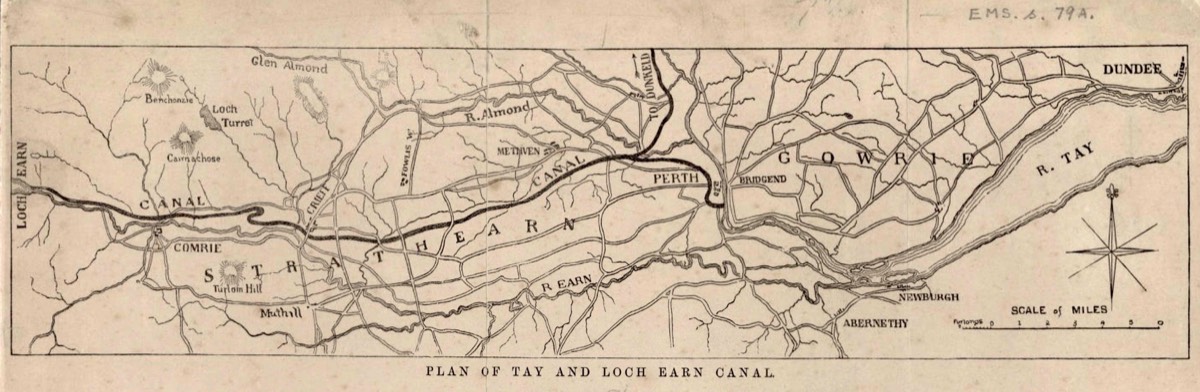

Plan of the proposed canal between Loch Earn and Perth, estimate ca. 1820 from The National Library of Scotland with thanks.

For the Strathearn part of the proposed canal, Stevenson’s route was as follows; the canal was to commence in the basin at Perth Harbour and progress to Craigie and then head due north approximately parallel to the line of the River Tay to its east, through Goodlyburn and Tulloch and run parallel to the River Almond. North of Huntingtower it would cross Huntingtower Haugh and then run westwards towards Methven, passing south of Culdeesland, then south-west by Tippermalloch, continue south of Redhill, passing Inchaffrey Abbey just to the north. The canal would then run parallel to the Pow Burn in a south-west direction through Woodend, Dollerie and Peathills, before turning north of Pittentian and travel in a north-west line to continue just north of Strathearn Campus, through what is now the Health Centre, cross King Street and so westwards, before swinging north to Milnab Mill and across the Turret Burn, and on towards Dalvreck crossroads. From Dalvreck it would turn south-west to Laggan, west to Trowan and swing due north to the Quoigs (Lower Quoigs). The canal was next proposed to run south of the road between Crieff and Comrie, thus minimising any disruption to the amenity of Lawers, Clathick and Tomperran estates, cross the road at Tomperran, and continue due west until Tullybannocher was reached. Keeping just to the north of the Comrie to St Fillans Road it would run due west to St Fillans, pass south of Crappich Wood, north of Dalchonzie and on into what was Little Port (now St.Fillans) and enter Loch Earn opposite Neish Island.

{Robert Stevenson, Engineer, who surveyed for a canal between Perth and Loch Earn in 1820. (Public domain Wikimedia)}

However, by 1820 when Stevenson’s report was published, railways were developing at a great pace, with new improvements to the steam engine resulting in them widely replacing horses to pull wagons and carriages, so many people now saw railways as the future.

In a report by the same Robert Stevenson, dated 14th of August 1826, he states,

‘Generally speaking, a canal, with an average portion of lockage, will be found to cost double, and in many instances quadruple, the expense of a well constructed railway; while the charges of trackage, or the transport of goods upon either, do not materially differ. On the canal, a horse may be estimated to work with 30 tons of goods and travel at a rate not exceeding 2 mph. On a level railway he will work with 10 ton and travel at 3 mph. However, in the management of the craft upon the canal three persons are usually required, but on the railway, the horse load is conducted by one person.’

From this report it was apparent that Railways were faster, more efficient, and importantly, cheaper to build and operate than canals and so Strathearn never got a canal after all the surveys. However, it was not until 15th August 1853, 83 years after James Watt’s initial survey, and after failed attempts in 1845 and 46 to get a railway, that the Crieff Junction Railway Company was authorised to build its line between Crieff Junction (Gleneagles) and Crieff, which opened for goods traffic on 14th March and to passengers on 16th March 1856. Eventually lines were also built linking Perth and Balquhidder, and it’s interesting to note that the line the railway took between Perth and Loch Earn, was almost the same line the canal would have followed – both forms of transport trying to find the more level ground. The railways went on to serve Crieff and Strathearn for the next 111 years.

Today the limekiln and the Manager’s House at St.Fillans , now incorporated into the Four Seasons Hotel, act as reminders, forming a lasting memorial to the lime-burning industry and the canal proposals of the early 18th century.

In a report by the same Robert Stevenson, dated 14th of August 1826, he states,

‘Generally speaking, a canal, with an average portion of lockage, will be found to cost double, and in many instances quadruple, the expense of a well constructed railway; while the charges of trackage, or the transport of goods upon either, do not materially differ. On the canal, a horse may be estimated to work with 30 tons of goods and travel at a rate not exceeding 2 mph. On a level railway he will work with 10 ton and travel at 3 mph. However, in the management of the craft upon the canal three persons are usually required, but on the railway, the horse load is conducted by one person.’

From this report it was apparent that Railways were faster, more efficient, and importantly, cheaper to build and operate than canals and so Strathearn never got a canal after all the surveys. However, it was not until 15th August 1853, 83 years after James Watt’s initial survey, and after failed attempts in 1845 and 46 to get a railway, that the Crieff Junction Railway Company was authorised to build its line between Crieff Junction (Gleneagles) and Crieff, which opened for goods traffic on 14th March and to passengers on 16th March 1856. Eventually lines were also built linking Perth and Balquhidder, and it’s interesting to note that the line the railway took between Perth and Loch Earn, was almost the same line the canal would have followed – both forms of transport trying to find the more level ground. The railways went on to serve Crieff and Strathearn for the next 111 years.

Today the limekiln and the Manager’s House at St.Fillans , now incorporated into the Four Seasons Hotel, act as reminders, forming a lasting memorial to the lime-burning industry and the canal proposals of the early 18th century.

{New Crieff Station as built in 1893, looking West from Duchlage Road bridge. The large goods shed seen top left was the original Crieff Railway Station. (Roger Maxwell)}

Earliest known photo of James Square, taken around 1860, before the town developed with the coming of the railway. (St Andrews University Collection)

Heavily patronised coach at St.Fillans, but reminiscent of the mail coaches which used to run through Strathearn. (St Andrews University Collection)

Lock 20 at Wyndford on the Forth & Clyde Canal, where people from Strathearn could transfer from the coach to canal as they journeyed to Glasgow. (Canmore)

Crieff Junction Station as built by the Crieff Junction and Scottish Central Railway Companies in 1856, looking North. This station was re-developed in 1912 to form Gleneagles Station. (David Ferguson Collection)

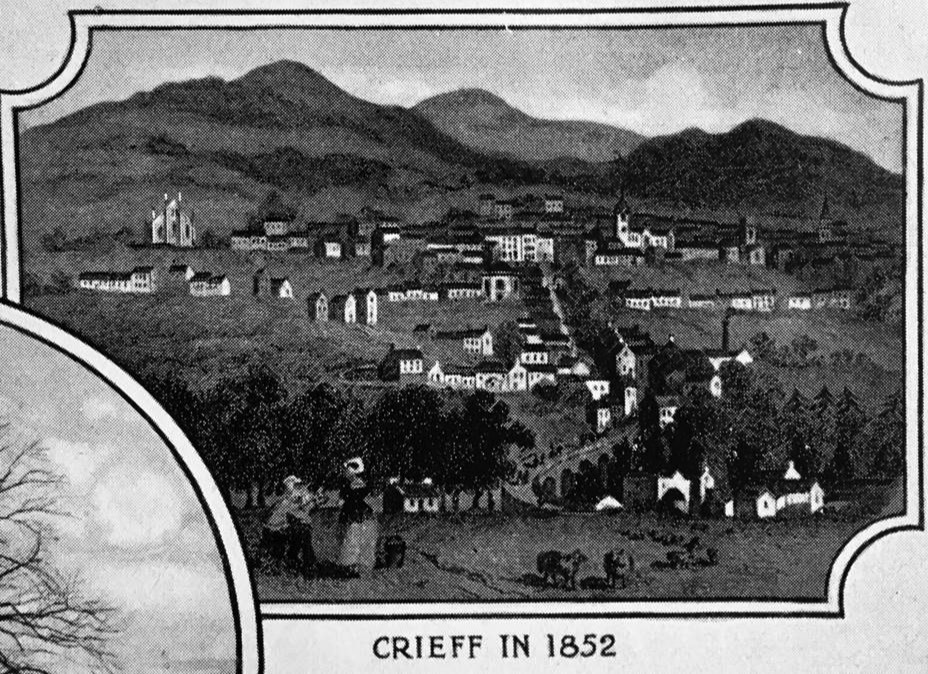

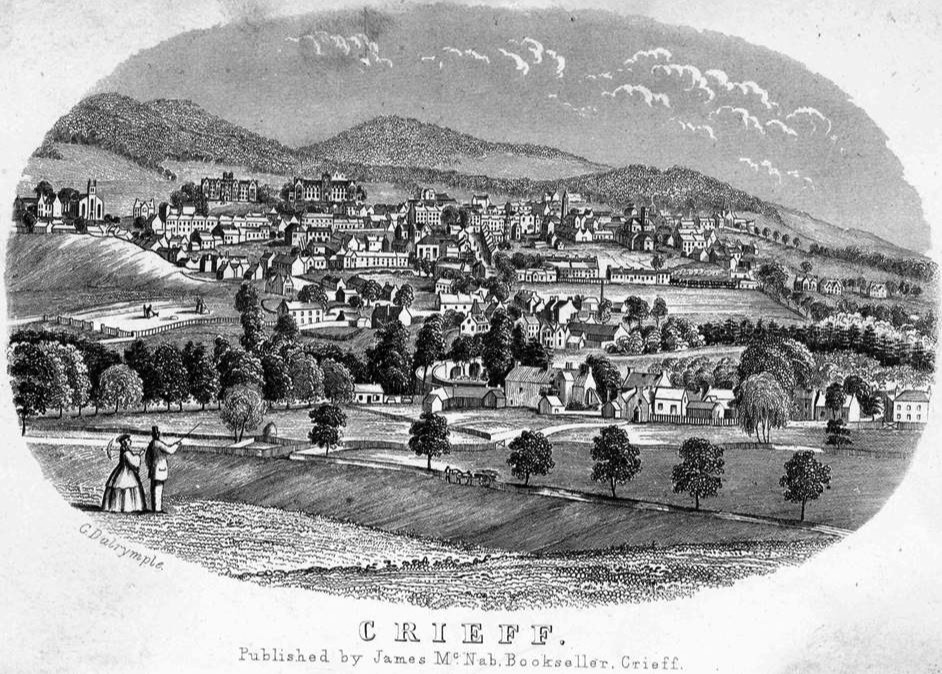

Engraving of Crieff in 1852, showing the town before development with the coming of the railway in 1856. Note Morrison’s Academy and Crieff Hydro yet to be built. (Alexander Porteous ‘History of Crieff’)

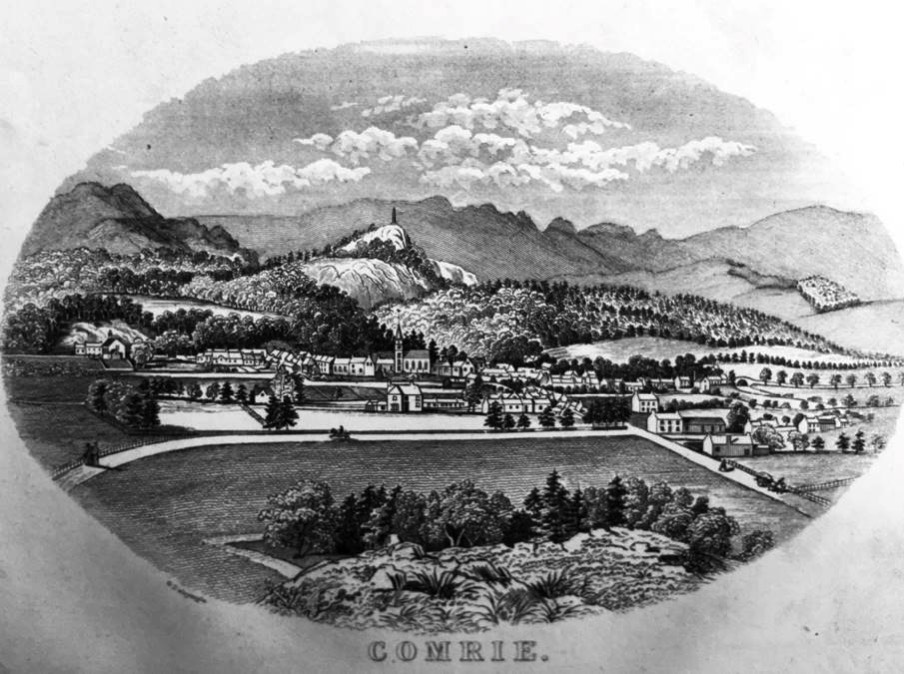

Engraving of Comrie, showing the village before development with the coming of the railway in 1893. (‘Guide Book to Crieff and the Vale of Strathearn’ published in 1862 – David Ferguson Collection)

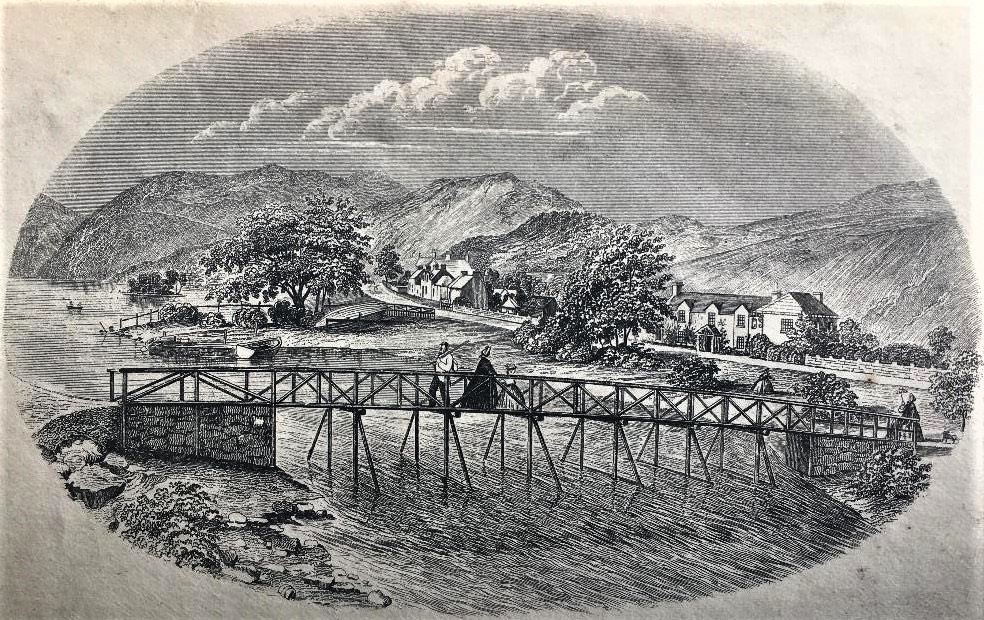

Engraving of St.Fillans, showing the village before development with the coming of the railway in 1901. (‘Guide Book to Crieff and the Vale of Strathearn’ published in 1862 – David Ferguson Collection)

Engraving of Crieff in 1872, showing the town starting to develop after the coming of the railway, with Morrison’s Academy – built in 1860, and Strathearn Hydropathic (Crieff Hydro) which opened in 1868. Drummond Arms Hotel yet to be built. (David Ferguson Collection)