From Moo to Mòd - The Story of Scotland's Drovers

tbc

This week [15/10/2022] sees the start of the 115th Royal National Mod which is being held in Perth this year. Many people do not realise that this grand competition may have had its origins from singing competitions held by the Drovers. Fittingly this week, in years gone by, would also have seen the largest of Scotland’s cattle markets until 1770, Crieff’s Michaelmas Fair or Market.

The early history of the droving industry is to a large extent the story of the gradual transition from lawless cattle driving to lawful cattle droving. The process of change began to be apparent about the end of the 15th century and gradually acquired momentum, with the Union of the Crowns in 1603 helping the trend towards the legitimate movement of livestock. However, it seems droving was one of the few sectors of the Scottish economy to benefit from the Union of Parliaments in 1707, as it was after this that droving in the sense of large-scale organised movement of livestock on foot to established markets became a marked feature of Scotland’s economy.

Scottish graziers had benefited from a ban by the English Parliament, in one of their Navigation Acts, on the import of Irish cattle after 1664. In 1663 18,000 cattle went south through Carlisle alone; in 1664 altogether nearly 48,000, as well as over 11,000 sheep went across the border to England. In the 1680s, when more regular figures became available, the peak year of animal exports to England was 1683 with 27,000 cattle annually, and 32,000 sheep. The sheep mostly originated in the Borders, where large flocks were becoming common, but for cattle their origin is unknown.

Records show that the Michaelmas Fair has been held in Crieff since 1632, although it may not have had a large sale in cattle at this time, but it’s almost certain much of the livestock noted crossing the Border into England, would have changed hands in Crieff.

In 1669, all export and import duties on cattle going to England were abolished, and the appointment in 1680 of a Commission for the encouragement of trade between the two countries marked the approach of new and better times. This change in the commercial relations of Scotland and England coincided very closely with the confirmation, by an Act of Parliament in 1672, to James, Earl of Perth, of the right to hold, ‘ane yeirlie fair and weiklie mercat’ at Crieff, a coincidence in which it is probable that mere chance played little part. For with the steady increase of cattle traffic to the south, the need had arisen for the concentration of the trade at some central point where buyers and sellers could easily come together, a need which the scattered local markets hitherto in existence could not meet.

In 1682 the Earl of Perth bought some ground at the west end of the Kirkton of Crieff from his relative, George Drummond, and set about developing it as a market area and building the tolbooth. He followed this up by buying more land from George on the lower slopes of the Knock, which became the cattle stance for the Fair and grazing for the cattle awaiting the sale.

Crieff Market

For centuries, Crieff had a number of local and weekly markets for selling and trading various goods but the main fairs were the Michaelmas Fair and St Thomas’s Fair, which was another old standing fair. On 17th July 1672 the Scots Parliament of King Charles II granted to James, Earl of Perth, permission to hold another fair. It was felt that this was necessary because there was too long a period from St Thomas’s Day Fair on 20th December, to the Michaelmas Fair on 11th October, and ‘Crieff is far remote and distant from any burgh Royal, and necessary it is for the ease and advantage of the Lieges that another yearly fair be added to the former (St.Thomas’ Day) to be held upon that part of the lands of Pittenzie within the said burgh of Crieff.’ This fair became known as St.Francis’ Fair, and was to be held on the third Tuesday of June.

The Michaelmas Tryst began on the 11th October and lasted for several days. There was quite a festival atmosphere, for on top of the cattle for sale, there were also all sorts of goods including boots, shoes, homespun yarn, cloth, tinware, and pails and tubs, while apple and pear carts and sweetie stands abounded. There were also entertainers such as jugglers and cheap-jacks aplenty.

Gaelic, Scots and English, among other languages, would have been heard, as cattle were herded, deals struck and the general hubbub of the Fair, not to mention barking dogs and mooing cattle!

In the following account, which was printed in the February edition of Eliakim Littell’s ‘Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art’, the dynamic spectacle of the Falkirk Tryst in 1838 is described in considerable detail, and is worth repeating at length to set the scene, as presumably Crieff would have been much the same:

‘The scene seen from horseback, from a cart, or some erection, is particularly imposing. All is animation, business, bustle, and activity. Servants running about shouting to the cattle, keeping them together in their particular lots, and ever and anon cudgels are at work upon the horns and rumps of the restless animals that attempt to wander in search of grass or water. The cattle dealers of all descriptions, chiefly on horseback, are scouring the field in search of the lots they require. The Scottish drovers are, for the most part, mounted on small, shaggy, spirited ponies, that are obviously quite at home among the cattle; and they carry their riders through the throngest groups with astonishing celerity … A good deal of haggling takes place; and, when the parties come to an agreement, the purchaser claps a penny of arles into the hand of the stockholder, observing at the same time “It’s a bargain.” Tar dishes are then got, and the purchaser’s mark being put upon the cattle, they are driven from the field. Besides numbers of shows, from 60 to 70 tents are erected along the field, for selling spirits and provisions … Many kindle fires at the end of their tents, over which cooking is briskly carried on. Broth is made in considerable quantities, and meets a ready sale. As most of the purchasers are paid in these tents they are constantly filled and surrounded with a mixed multitude of cattle dealers, fishers, drovers, auctioneers, pedlars, jugglers, gamblers, itinerant fruit merchants, ballad singers and beggars. What an indescribable clamour prevails in most of these party-coloured abodes! Far in the afternoon, when frequent calls have elevated the spirits and stimulated the colloquial powers of the visitors, a person hears an uncouth Cumberland jargon, and the prevailing Gaelic, along with the innumerable provincial dialects, in their genuine purity, mingled in one astounding roar. All seem inclined to speak; and raising their voices to command attention, the whole of the orators are consequently obliged to bellow as loud as they can possibly roar. When the cattle dealers are in the way of their business, their conversation is full of animation, and their technical phrases are generally appropriate and highly amusing.’

In his account from 1723 of ‘A Journey Through Scotland’, John Macky visited Crieff and tells of there being ‘at least 30,000 cattle sold there, most of them to English Drovers; who paid down above 30,000 Guineas in ready money to the Highlanders; a Sum they had never seen before, and proves one good effect of the Union.’

In many cases payment for the cattle at the market would be in bills rather than cash. When James Boswell and Samuel Johnson visited Skye in 1772, they found that the rents due to the Lairds were paid in drovers’ bills. A system of finance based largely on bills of exchange seems to have been general throughout the Highlands at that time. Many of these Highland bills were made payable at Crieff, for during the first half of the 18th century Crieff cattle market was probably the greatest centre of money circulation in the country. Considerable sums, however, also changed hands in the form of gold as Macky described in his account, and an entry in the Minute Book of the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1730 shows that tellers were that year sent from Edinburgh to Crieff with £3,000 in notes to put into circulation, in return for cash.

Horses were sold too and apparently in some parts of the Highlands, the horses were taught English as well as Gaelic so that if they were sold to the Lowlands they could understand the commands of their new Masters. About 1790 the price of Highland ponies was between £4 and £6.

The Earl of Perth also benefitted from the tolls and fair dues he exacted. In 1734 the receipts from fair dues were £600 Scots, £67 sterling, with the maximum figure recorded, being £83 in 1755. Even in 1763, in the early years of its decline, this Fair still accounted for over 80% of the tolls collected in that year.

At the Michaelmas Fair cattle sellers paid 13s.4d. Scots for every 20 beasts brought to the market, approximately 8d. Scots per head. This money was usually collected on the day of the Fair but attempts were made in the declining years of the Fair to uplift payment eight days before and after the Fair day, so that drovers who were simply passing through the town would be liable to pay the toll. Upwards of twenty men were employed to collect the tariffs, strategically placed on the roads leading into Crieff. One of the collecting stations was on the main road near Monzie, making it difficult for Highland traffic travelling south through the Sma' Glen to evade payment. Fair customs not only became an integral part of an estate rental, but also attracted individuals to bid for the right to collect the revenue.

There is little published information available describing how the trysts were structured, but it is likely that the buying and selling of cattle would have occurred throughout the day, rather than at particular times. For the greater period of the tryst’s existence there were no auctioneers, so business had to be done directly between herdsmen and dealers.

The Michaelmas Tryst began on the 11th October and lasted for several days. There was quite a festival atmosphere, for on top of the cattle for sale, there were also all sorts of goods including boots, shoes, homespun yarn, cloth, tinware, and pails and tubs, while apple and pear carts and sweetie stands abounded. There were also entertainers such as jugglers and cheap-jacks aplenty.

Gaelic, Scots and English, among other languages, would have been heard, as cattle were herded, deals struck and the general hubbub of the Fair, not to mention barking dogs and mooing cattle!

In the following account, which was printed in the February edition of Eliakim Littell’s ‘Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art’, the dynamic spectacle of the Falkirk Tryst in 1838 is described in considerable detail, and is worth repeating at length to set the scene, as presumably Crieff would have been much the same:

‘The scene seen from horseback, from a cart, or some erection, is particularly imposing. All is animation, business, bustle, and activity. Servants running about shouting to the cattle, keeping them together in their particular lots, and ever and anon cudgels are at work upon the horns and rumps of the restless animals that attempt to wander in search of grass or water. The cattle dealers of all descriptions, chiefly on horseback, are scouring the field in search of the lots they require. The Scottish drovers are, for the most part, mounted on small, shaggy, spirited ponies, that are obviously quite at home among the cattle; and they carry their riders through the throngest groups with astonishing celerity … A good deal of haggling takes place; and, when the parties come to an agreement, the purchaser claps a penny of arles into the hand of the stockholder, observing at the same time “It’s a bargain.” Tar dishes are then got, and the purchaser’s mark being put upon the cattle, they are driven from the field. Besides numbers of shows, from 60 to 70 tents are erected along the field, for selling spirits and provisions … Many kindle fires at the end of their tents, over which cooking is briskly carried on. Broth is made in considerable quantities, and meets a ready sale. As most of the purchasers are paid in these tents they are constantly filled and surrounded with a mixed multitude of cattle dealers, fishers, drovers, auctioneers, pedlars, jugglers, gamblers, itinerant fruit merchants, ballad singers and beggars. What an indescribable clamour prevails in most of these party-coloured abodes! Far in the afternoon, when frequent calls have elevated the spirits and stimulated the colloquial powers of the visitors, a person hears an uncouth Cumberland jargon, and the prevailing Gaelic, along with the innumerable provincial dialects, in their genuine purity, mingled in one astounding roar. All seem inclined to speak; and raising their voices to command attention, the whole of the orators are consequently obliged to bellow as loud as they can possibly roar. When the cattle dealers are in the way of their business, their conversation is full of animation, and their technical phrases are generally appropriate and highly amusing.’

In his account from 1723 of ‘A Journey Through Scotland’, John Macky visited Crieff and tells of there being ‘at least 30,000 cattle sold there, most of them to English Drovers; who paid down above 30,000 Guineas in ready money to the Highlanders; a Sum they had never seen before, and proves one good effect of the Union.’

In many cases payment for the cattle at the market would be in bills rather than cash. When James Boswell and Samuel Johnson visited Skye in 1772, they found that the rents due to the Lairds were paid in drovers’ bills. A system of finance based largely on bills of exchange seems to have been general throughout the Highlands at that time. Many of these Highland bills were made payable at Crieff, for during the first half of the 18th century Crieff cattle market was probably the greatest centre of money circulation in the country. Considerable sums, however, also changed hands in the form of gold as Macky described in his account, and an entry in the Minute Book of the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1730 shows that tellers were that year sent from Edinburgh to Crieff with £3,000 in notes to put into circulation, in return for cash.

Horses were sold too and apparently in some parts of the Highlands, the horses were taught English as well as Gaelic so that if they were sold to the Lowlands they could understand the commands of their new Masters. About 1790 the price of Highland ponies was between £4 and £6.

The Earl of Perth also benefitted from the tolls and fair dues he exacted. In 1734 the receipts from fair dues were £600 Scots, £67 sterling, with the maximum figure recorded, being £83 in 1755. Even in 1763, in the early years of its decline, this Fair still accounted for over 80% of the tolls collected in that year.

At the Michaelmas Fair cattle sellers paid 13s.4d. Scots for every 20 beasts brought to the market, approximately 8d. Scots per head. This money was usually collected on the day of the Fair but attempts were made in the declining years of the Fair to uplift payment eight days before and after the Fair day, so that drovers who were simply passing through the town would be liable to pay the toll. Upwards of twenty men were employed to collect the tariffs, strategically placed on the roads leading into Crieff. One of the collecting stations was on the main road near Monzie, making it difficult for Highland traffic travelling south through the Sma' Glen to evade payment. Fair customs not only became an integral part of an estate rental, but also attracted individuals to bid for the right to collect the revenue.

There is little published information available describing how the trysts were structured, but it is likely that the buying and selling of cattle would have occurred throughout the day, rather than at particular times. For the greater period of the tryst’s existence there were no auctioneers, so business had to be done directly between herdsmen and dealers.

tbc

The Journeys

Cattle passing through Callander

Macky's estimate of 30,000 cattle may be no wild exaggeration, because another traveller, Robert Forbes, the Episcopal bishop of Ross and Caithness, encountered a sizeable number of beasts, headed for Crieff, in 1762. The Bishop noted in his travel journal how he met eight droves totalling 1,200 beasts at Dalwhinnie, followed by another drove a mile-long in the Drumochter Pass and 300 more beasts resting at the mouth of Loch Garry. His account not only helps to emphasise the volume of the cattle traffic passing through the districts of Badenoch and Atholl up to a month before the Fair at Crieff, but also shows that the Highland drovers moved their cattle southwards at a slow, leisurely pace allowing them to graze as they moved along, and usually stopped their animals for a mid-day rest after four hours on the hoof. The Drovers had every intention of maintaining and even improving the condition of the animals before market, so maximising their value for the sales.

A drover from the Flodigarry and Kingsburgh Estates in north Skye, around 220 miles from Crieff, described to Bishop Forbes how every drove had up to four men and some boys to look after the cattle. He also informed the Bishop that when the drove was large it was the custom to subdivide the animals into smaller groups, making it easier to handle the cattle in narrow passes and on bridges. Of all the trackways that the cattle drovers followed to reach the trysts or markets, the journey from the Isle of Skye to Crieff, was the most dangerous and difficult. The cattle covered up to twelve miles a day, though the actual distance must have varied with the terrain and the weather conditions.

Martin Martin, writing of the islands at the end of the 1600’s, showed that cattle were being swum across the Kyle Reay tied nose to tail in groups of five, and the Harris Estate of the McLeod’s was aware that the price of cattle determined the ability to pay rents. Although both Crieff and Falkirk had long been eclipsed as markets, it is believed that the last herd of cattle swam across the Kyle Rhea narrows in 1906, although during the boom times, around 8,000 cattle a year were swum across the Kyle Reay narrows to the mainland.

The expansion of the cattle trade, by increasing the payment of rent in money, met the need of the chiefs for higher spending power. Highland chiefs were making use of Lowland education and sometimes of state offices, which might include the command of a Highland company for peace-keeping purposes. They were purchasing luxuries that could not be produced in the Highlands, and they might move about in the Lowlands, when they had enough cash, as ordinary gentry. Therefore the onus was more firmly being placed on the tenant to pay the rent in money, rather than in kind.

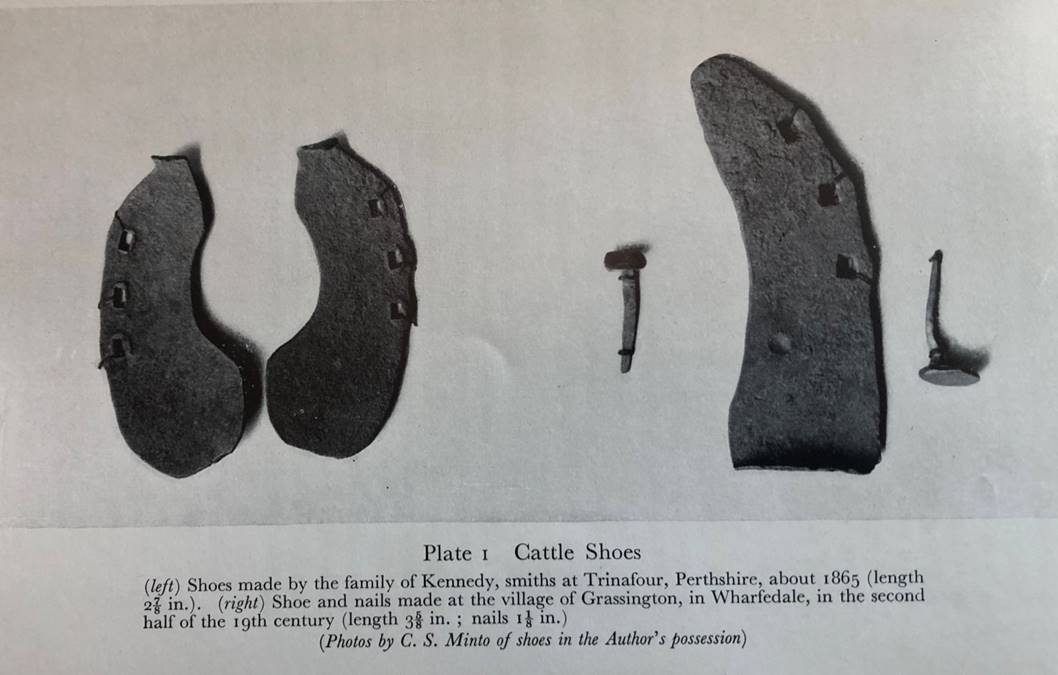

Cattle formed the greatest part of the wealth of the Highlands. Rents and wages were often paid in kind and little real money circulated. However with the chiefs demanding rent in money, more cattle had to go the fairs, and went on the hoof under the charge of the Drover. He sold them on behalf of the owner, or sometimes bought them for himself, often not paying for them till they were resold. As the beasts journeyed south they would finally leave the soft, grassy drove roads and come to the hard military roads, where they were then shod to protect their feet.

This could be difficult as the beasts were half-wild and had to be thrown onto their backs. Each hoof required two small shoes; one for each half of the cloven foot, although plating of the inner half of the hoof was not always considered necessary.

ARB Haldane mentions that even in the 1930’s there still lived men who could remember the shoeing of cattle at a smiddy at Trinafour, near Loch Errochty and Blair Atholl, on the main drove road to Crieff from the North, and Tyndrum.

The droves which had reached the Perthshire county boundary near Tyndrum moved on down the long glen of the Dochart, many of them reaching Crieff by way of Glen Ogle and the side of Loch Earn, though according to local tradition a route from Ledcharrie in Glen Dochart over the hills to Balquidder was also used. Some may have chosen the route by Loch Tay. For these, the route led along the south side of the Loch to Ardeonaig where they climbed southward through the hills and so came into Glen Lednock. Local tradition tells of a considerable cattle traffic coming from Loch Tay, crossing from Glen Lednock,near Innergeldie, into Glen Boltachan and so reaching the valley of the Earn near St.Fillans.

A second stream of cattle would converge on Crieff from the north and north-east by moving through the Sma’ Glen from the direction of Amulree and the valley of the Tay at Dunkeld.

However for some Drovers, reaching Crieff may not have been the end of their journey, as some dealers might bargain with the Highlanders to drive the cattle on to England for a wage of perhaps only one shilling per day.

A drover from the Flodigarry and Kingsburgh Estates in north Skye, around 220 miles from Crieff, described to Bishop Forbes how every drove had up to four men and some boys to look after the cattle. He also informed the Bishop that when the drove was large it was the custom to subdivide the animals into smaller groups, making it easier to handle the cattle in narrow passes and on bridges. Of all the trackways that the cattle drovers followed to reach the trysts or markets, the journey from the Isle of Skye to Crieff, was the most dangerous and difficult. The cattle covered up to twelve miles a day, though the actual distance must have varied with the terrain and the weather conditions.

Martin Martin, writing of the islands at the end of the 1600’s, showed that cattle were being swum across the Kyle Reay tied nose to tail in groups of five, and the Harris Estate of the McLeod’s was aware that the price of cattle determined the ability to pay rents. Although both Crieff and Falkirk had long been eclipsed as markets, it is believed that the last herd of cattle swam across the Kyle Rhea narrows in 1906, although during the boom times, around 8,000 cattle a year were swum across the Kyle Reay narrows to the mainland.

The expansion of the cattle trade, by increasing the payment of rent in money, met the need of the chiefs for higher spending power. Highland chiefs were making use of Lowland education and sometimes of state offices, which might include the command of a Highland company for peace-keeping purposes. They were purchasing luxuries that could not be produced in the Highlands, and they might move about in the Lowlands, when they had enough cash, as ordinary gentry. Therefore the onus was more firmly being placed on the tenant to pay the rent in money, rather than in kind.

Cattle formed the greatest part of the wealth of the Highlands. Rents and wages were often paid in kind and little real money circulated. However with the chiefs demanding rent in money, more cattle had to go the fairs, and went on the hoof under the charge of the Drover. He sold them on behalf of the owner, or sometimes bought them for himself, often not paying for them till they were resold. As the beasts journeyed south they would finally leave the soft, grassy drove roads and come to the hard military roads, where they were then shod to protect their feet.

This could be difficult as the beasts were half-wild and had to be thrown onto their backs. Each hoof required two small shoes; one for each half of the cloven foot, although plating of the inner half of the hoof was not always considered necessary.

ARB Haldane mentions that even in the 1930’s there still lived men who could remember the shoeing of cattle at a smiddy at Trinafour, near Loch Errochty and Blair Atholl, on the main drove road to Crieff from the North, and Tyndrum.

The droves which had reached the Perthshire county boundary near Tyndrum moved on down the long glen of the Dochart, many of them reaching Crieff by way of Glen Ogle and the side of Loch Earn, though according to local tradition a route from Ledcharrie in Glen Dochart over the hills to Balquidder was also used. Some may have chosen the route by Loch Tay. For these, the route led along the south side of the Loch to Ardeonaig where they climbed southward through the hills and so came into Glen Lednock. Local tradition tells of a considerable cattle traffic coming from Loch Tay, crossing from Glen Lednock,near Innergeldie, into Glen Boltachan and so reaching the valley of the Earn near St.Fillans.

A second stream of cattle would converge on Crieff from the north and north-east by moving through the Sma’ Glen from the direction of Amulree and the valley of the Tay at Dunkeld.

However for some Drovers, reaching Crieff may not have been the end of their journey, as some dealers might bargain with the Highlanders to drive the cattle on to England for a wage of perhaps only one shilling per day.

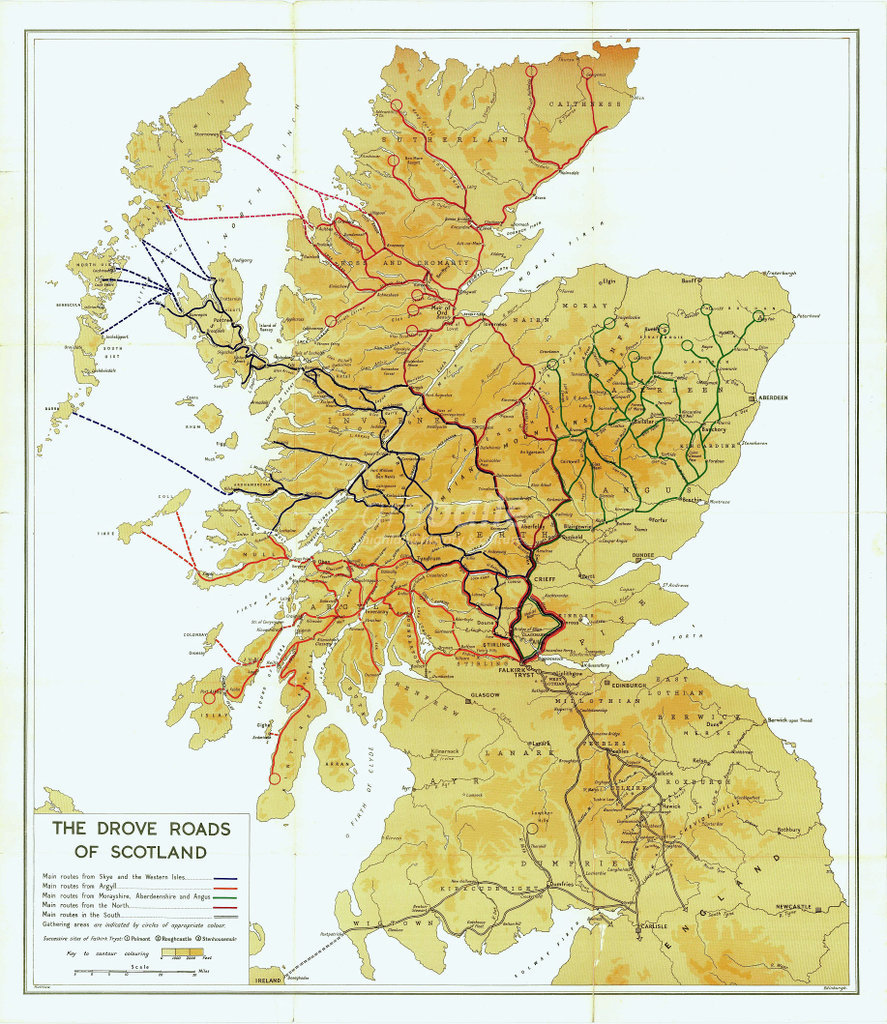

The attached map from "The Drove Roads of Scotland" by A R B Haldane (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd: 1952)

Plate 1 from "The Drove Roads of Scotland" by A R B Haldane (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd: 1952)

Crieff & Strathearn Museum would love to hear from anyone who has a set of these cattle shoes, and would like to donate them or sell them.

Highlandman station, looking north, 1961 - David Ferguson Collection

The drover's life

Cattle droving could be a very fickle business; the Drover had cause for grave thought and anxious calculation, for his was a complex budget in which many of the items were unpredictable and imponderable. A Drover bringing beasts from the Outer Islands had in the first place to reckon with the cost and risk of ferrying them to the mainland. Feeding on the cross-country journey cost him little or nothing in the hill country, but in the Lowland districts, and near the Trysts, he was forced, increasingly as the 18th century wore on, to pay for his rights of stance and nightly grazing. Market dues at Crieff were around 2d a beast for cattle, and by 1834 in Falkirk they were 8d a score for cattle and 3d a score for sheep, payable to Sir Michael Bruce, the owner of the Falkirk Tryst ground, who let the right of collecting the tolls to a Tacksman at a rent of £120 per annum. Early in the 18th century the pay of a working drover appears to have amounted to only 1s a day, but gradually this increased, reaching 3s or 4s a day in the first half of the 19th century. It should be borne in mind however, that the drover had to return home at his own expense.

By day there were bogs to be avoided; rivers which were quick to rise; the feet of the cattle to be attended to; and resting places with pasture and water to be found - essential if the beasts were to reach the market in good condition. Rough shelters for the Drovers came into being at these stances; the most useful of them later became simple booths where accommodation and food were to be had. Basic foodstuffs such as oatmeal might be carried to make porridge and oat cakes over a fire. Potatoes provided a good broth which could be augmented with any game or vegetables to be got along the way, or even the odd fresh trout from the burn.

The disorderly conduct of some of the Highlanders was long remembered in the neighbourhood of Crieff, and Mr Laurie, the School-master of Monzie, who wrote the Statistical Account of that Parish, said that they were ‘described by people old enough to remember them, as barefooted, and bareheaded, although many of them old men. Being numerous, they used to enter the houses of the country people, take unceremonious possession of their firesides and beds, carry off the potatoes from their fields and gardens, and sometimes even the blankets which had afforded them a temporary covering for the night.’

By day there were bogs to be avoided; rivers which were quick to rise; the feet of the cattle to be attended to; and resting places with pasture and water to be found - essential if the beasts were to reach the market in good condition. Rough shelters for the Drovers came into being at these stances; the most useful of them later became simple booths where accommodation and food were to be had. Basic foodstuffs such as oatmeal might be carried to make porridge and oat cakes over a fire. Potatoes provided a good broth which could be augmented with any game or vegetables to be got along the way, or even the odd fresh trout from the burn.

The disorderly conduct of some of the Highlanders was long remembered in the neighbourhood of Crieff, and Mr Laurie, the School-master of Monzie, who wrote the Statistical Account of that Parish, said that they were ‘described by people old enough to remember them, as barefooted, and bareheaded, although many of them old men. Being numerous, they used to enter the houses of the country people, take unceremonious possession of their firesides and beds, carry off the potatoes from their fields and gardens, and sometimes even the blankets which had afforded them a temporary covering for the night.’

Jacobites and the fair

Due to the nature of the Michaelmas Fair drawing large crowds from all sections of society, it was an ideal location for clandestine meetings of those loyal to the Jacobite cause. Here at the Fair they could mingle with the crowd and exchange details and documents without causing suspicion for themselves. Even after the battle of Culloden in 1746, some factions continued to fight the cause. For example, in 1752 under the Elibank Plot , some Scottish Chiefs and other Jacobite leaders were supposedly to meet up with other plotters at Crieff Tryst, where a large cache of arms was also meant to be located to furnish the conflict, and so further their aims.

However, the Rising of 1745 seems not to have affected Crieff Tryst seriously, for a Dumfriesshire cattle dealer is noted writing to his partner in 1746 referring to a rival having gone to Crieff to buy several thousand beasts; and references by the commanders of English garrisons stationed in the Highlands, immediately after the Rising, to thefts of cattle on the way to Crieff, show that the troubles of the times had not deterred, some at least, of the Drovers. The Rising had, however, a more serious, if less immediate effect on Crieff Tryst. Hitherto the trade with England in Scots cattle had been largely in the hands of Scotsmen. The more peaceful times and the higher cattle prices which followed the failure of the Rising, brought English dealers increasingly to the Scots cattle markets after the middle of the century to share directly in the trade. This in turn meant the need for a market more convenient to them, and in conjunction with the increasing cost of droving and the need to adopt the quickest routes to market, led to the eventual eclipse of Crieff by Falkirk, which remained till the end of the cattle droving industry the greatest cattle tryst in Scotland.

However, the Rising of 1745 seems not to have affected Crieff Tryst seriously, for a Dumfriesshire cattle dealer is noted writing to his partner in 1746 referring to a rival having gone to Crieff to buy several thousand beasts; and references by the commanders of English garrisons stationed in the Highlands, immediately after the Rising, to thefts of cattle on the way to Crieff, show that the troubles of the times had not deterred, some at least, of the Drovers. The Rising had, however, a more serious, if less immediate effect on Crieff Tryst. Hitherto the trade with England in Scots cattle had been largely in the hands of Scotsmen. The more peaceful times and the higher cattle prices which followed the failure of the Rising, brought English dealers increasingly to the Scots cattle markets after the middle of the century to share directly in the trade. This in turn meant the need for a market more convenient to them, and in conjunction with the increasing cost of droving and the need to adopt the quickest routes to market, led to the eventual eclipse of Crieff by Falkirk, which remained till the end of the cattle droving industry the greatest cattle tryst in Scotland.

tbc

tbc

Decline and Falkirk's rise

Shortly after 1750 various factors undermined the importance of Crieff as a cattle market and led ultimately to the transference of the main trade to Falkirk Tryst. By the last decade of the century, though many thousands of cattle were still using the route through the Sma’ Glen to Crieff, they passed the town on the day before the date fixed for the Tryst, so avoiding the market dues which were still levied. By this time Crieff had shrunk to a mere shadow of what it once had been. A little way down-stream from Crieff, Dalpatrick Ford crosses the River Earn. The ford is on the direct line of Highlandman’s Loan from Gilmerton, where the Sma’ Glen road emerges from the hills. The name of ‘Highlandman’ can still be seen on the old railway station nearby, which opened in 1856, where the railway company hoped to tap into the droving trade and the livestock could be put onto trains for the remainder of their journey to market. Unfortunately it was not to be, as other stations opened further north, east and west around the same time, so absorbing the herds and flocks before they reached Highlandman. At Dalpatrick Ford the droves crossed the Earn and came into Strathallan by way of Muthill and the Muir of Orchill, and so on to Falkirk. As time wore on. Sheep began to dominate the market rather than cattle, so it was mainly sheep that would have been driven down Highlandman’s Loan.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century the sheep traffic passing over the drove roads of Scotland showed a steady increase. Falkirk Tryst had displaced Crieff shortly after the introduction of large-scale sheep farming, and here the number of sheep brought to the Tryst, as recorded in the local press of the day, shows clearly the rapid rise of the new stock farming. An agricultural report of 1812 estimated the number of sheep sold at Falkirk that year at 40,000. Six years later in 1818, at a newly established market in Inverness, 150,000 sheep were reported to have been sold. At the Falkirk Tryst of October 1836 the number sold there had grown to 75,000, and before the middle of the century when the numbers at the September and October markets had almost reached 200,000, the trade in sheep is reported to have surpassed the trade in cattle. From then onwards, though the increase in Highland sheep farming was to continue for another 25 years, the growth of the railways caused a gradual decline in the traffic on the drove roads.

The reasons for the decline of Crieff Tryst was symptomatic of a widespread and permanent change which had set in affecting by degrees the whole of the country cultivated or capable of cultivation. In some parts this took the form of the enclosing of pasture and arable fields by dry-stone dykes. In other places the Drovers routes were themselves enclosed by dykes or turf walls to protect the arable grounds through which they passed. Everywhere the Drovers were coming to be more narrowly hedged in and deprived increasingly of the wayside grazing which had hitherto been their traditional and unchallenged right.

The Statistical Account for Crieff in 1794 notes, ‘For a considerable time after the beginning of the century, the drovers from Argyll, Inverness, Ross shire, etc, paid nothing for the pasturing of their cattle on the way to market; but in the improved state of the country, grass became more valuable, the roads more confined, and the drovers were forced to enquire after the most convenient and cheap roads from their several homes to the principal marketplace now at Falkirk.‘

The imposition of increased custom tariffs, however, lay at the core of the drovers' real grievances. Revenue doubled after the Custom Collectors exacted a toll on cattle brought to the Fair, and a new additional toll on sold cattle. This particular toll most likely led to the boycott of Crieff by the Drovers and the dealers. As late as 1773 local heritors believed that if lower custom rates were fixed and collected directly by the factor, the decline of the Fair might be reversed.

The other main issue was highlighted by Lt. John Grant of Lurg, a Scottish Drover of the later eighteenth century and a regular traveller through Crieff, who recalled how the English cattle dealers deserted the town and insisted that the Drovers bring the cattle south to Falkirk in the 1760s.

Curiously, in less than twenty years the blame for the decline of the Fair was shifted from the Highland Drovers to the English dealers! The disenchantment of the Drovers may have showed its first signs in the early 1740s when land on the edge of the town at Culcrieff - traditionally used for grazing drove cattle - was enclosed to form parks, subdivided by inner dykes and eventually cultivated. By the late 1770s there were even plans to enclose and plant the site of the Fair stance.

The Falkirk Tryst was held around the same time as the Crieff Fair. It’s been suggested that the Falkirk Tryst developed from an informal agreement by cattle dealers to meet buyers there. This suggestion could be correct because neither the Tryst itself nor its approximate dates are recorded in the Falkirk burgh charters which date back to the beginning of the 17th century. Throughout its history the Falkirk Tryst was never authorised by Act of Parliament. By 1716 the Falkirk Tryst was held on muirland near Polmont, and remained at this venue until it moved to near Rough Castle in the early 1770’s, and finally Stenhousemuir in 1785. In spite of this documented history the Falkirk Tryst is omitted from lists of fairs in almanacs until the early 1770’s.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century the sheep traffic passing over the drove roads of Scotland showed a steady increase. Falkirk Tryst had displaced Crieff shortly after the introduction of large-scale sheep farming, and here the number of sheep brought to the Tryst, as recorded in the local press of the day, shows clearly the rapid rise of the new stock farming. An agricultural report of 1812 estimated the number of sheep sold at Falkirk that year at 40,000. Six years later in 1818, at a newly established market in Inverness, 150,000 sheep were reported to have been sold. At the Falkirk Tryst of October 1836 the number sold there had grown to 75,000, and before the middle of the century when the numbers at the September and October markets had almost reached 200,000, the trade in sheep is reported to have surpassed the trade in cattle. From then onwards, though the increase in Highland sheep farming was to continue for another 25 years, the growth of the railways caused a gradual decline in the traffic on the drove roads.

The reasons for the decline of Crieff Tryst was symptomatic of a widespread and permanent change which had set in affecting by degrees the whole of the country cultivated or capable of cultivation. In some parts this took the form of the enclosing of pasture and arable fields by dry-stone dykes. In other places the Drovers routes were themselves enclosed by dykes or turf walls to protect the arable grounds through which they passed. Everywhere the Drovers were coming to be more narrowly hedged in and deprived increasingly of the wayside grazing which had hitherto been their traditional and unchallenged right.

The Statistical Account for Crieff in 1794 notes, ‘For a considerable time after the beginning of the century, the drovers from Argyll, Inverness, Ross shire, etc, paid nothing for the pasturing of their cattle on the way to market; but in the improved state of the country, grass became more valuable, the roads more confined, and the drovers were forced to enquire after the most convenient and cheap roads from their several homes to the principal marketplace now at Falkirk.‘

The imposition of increased custom tariffs, however, lay at the core of the drovers' real grievances. Revenue doubled after the Custom Collectors exacted a toll on cattle brought to the Fair, and a new additional toll on sold cattle. This particular toll most likely led to the boycott of Crieff by the Drovers and the dealers. As late as 1773 local heritors believed that if lower custom rates were fixed and collected directly by the factor, the decline of the Fair might be reversed.

The other main issue was highlighted by Lt. John Grant of Lurg, a Scottish Drover of the later eighteenth century and a regular traveller through Crieff, who recalled how the English cattle dealers deserted the town and insisted that the Drovers bring the cattle south to Falkirk in the 1760s.

Curiously, in less than twenty years the blame for the decline of the Fair was shifted from the Highland Drovers to the English dealers! The disenchantment of the Drovers may have showed its first signs in the early 1740s when land on the edge of the town at Culcrieff - traditionally used for grazing drove cattle - was enclosed to form parks, subdivided by inner dykes and eventually cultivated. By the late 1770s there were even plans to enclose and plant the site of the Fair stance.

The Falkirk Tryst was held around the same time as the Crieff Fair. It’s been suggested that the Falkirk Tryst developed from an informal agreement by cattle dealers to meet buyers there. This suggestion could be correct because neither the Tryst itself nor its approximate dates are recorded in the Falkirk burgh charters which date back to the beginning of the 17th century. Throughout its history the Falkirk Tryst was never authorised by Act of Parliament. By 1716 the Falkirk Tryst was held on muirland near Polmont, and remained at this venue until it moved to near Rough Castle in the early 1770’s, and finally Stenhousemuir in 1785. In spite of this documented history the Falkirk Tryst is omitted from lists of fairs in almanacs until the early 1770’s.

The legacy

The Drovers enriched the country economically and culturally, and they left a legacy of many tracks and roads through beautiful countryside. Perhaps they formed the beginnings of what has become the Royal National MOD.

On reaching the market at Crieff or Falkirk, the Drovers could breathe a huge sigh of relief, with all the trials and tribulations of the journey behind them. At last they could relax and meet up with other Drovers and old friends and have a drink, sing songs, dance, play music and write and recite poetry.

On occasion this could lead to friendly rivalry and competitions, especially with the singing, dancing and playing music, and some scholars believe these competitions could have given rise into the origins of what is now the Royal National Mod. The Mod is Scotland’s premier Gaelic festival providing opportunities for people of all ages to perform across a range of competitive disciplines, including Gaelic music and song, highland dancing, instrumental, drama, sport and leisure.

Thanks to the Drovers, Scotland has a wealth of folk tales, poems and songs saved for posterity, and many of them now feature in our national competition.

SONG, FOR A HIGHLAND DROVER, RETURNING FROM ENGLAND (1801)

Now, fare thee well England; no further I’ll roam,

But follow my shadow, that points the way home;

Your gay southern shores shall not tempt me to stay,

For my Maggy’s at home, and my children at play;

’Tis this makes my bonnet sit light on my brow,

Gives my sinews their strength, and my bosom its glow.

Farewell, mountaineers! my companions, adieu!

Soon, many long miles when I’m sever’d from you,

I shall miss your white Horns on the brink of the Bourne,

And o’er the rough heaths, where you’ll never return;

But in brave English pastures you cannot complain,

While your Drover speeds back to his Maggy again.

O Tweed! gentle Tweed, as I pass your green vales,

More than life, more than love, my tir’d Spirit inhales;

There Scotland, my darling, lies full in my view;

With her barefooted lasses, and mountains so blue;

To the mountains away! my heart bounds like the hind;

For home is so sweet, and my Maggy so kind.

As day after day I still follow my course,

And in fancy trace back every stream to its source,

Hope cheers me up hills, where the road lies before,

O’er hills just as high, and o’er tracks of wild moor;

The keen polar star nightly rising to view;

But Maggy’s my Star, just as steady and true.

O Ghosts of my fathers! O Heroes, look down;

Fix my wandering thoughts on your deeds of renown;

For the glory of Scotland reigns warm in my breast,

And fortitude grows both from toil and from rest;

May your deeds and your worth be for ever in view,

And may Maggy bear sons not unworthy of you.

Love, why do you urge me, so weary and poor?

I cannot step faster, I cannot do more;

On reaching the market at Crieff or Falkirk, the Drovers could breathe a huge sigh of relief, with all the trials and tribulations of the journey behind them. At last they could relax and meet up with other Drovers and old friends and have a drink, sing songs, dance, play music and write and recite poetry.

On occasion this could lead to friendly rivalry and competitions, especially with the singing, dancing and playing music, and some scholars believe these competitions could have given rise into the origins of what is now the Royal National Mod. The Mod is Scotland’s premier Gaelic festival providing opportunities for people of all ages to perform across a range of competitive disciplines, including Gaelic music and song, highland dancing, instrumental, drama, sport and leisure.

Thanks to the Drovers, Scotland has a wealth of folk tales, poems and songs saved for posterity, and many of them now feature in our national competition.

SONG, FOR A HIGHLAND DROVER, RETURNING FROM ENGLAND (1801)

Now, fare thee well England; no further I’ll roam,

But follow my shadow, that points the way home;

Your gay southern shores shall not tempt me to stay,

For my Maggy’s at home, and my children at play;

’Tis this makes my bonnet sit light on my brow,

Gives my sinews their strength, and my bosom its glow.

Farewell, mountaineers! my companions, adieu!

Soon, many long miles when I’m sever’d from you,

I shall miss your white Horns on the brink of the Bourne,

And o’er the rough heaths, where you’ll never return;

But in brave English pastures you cannot complain,

While your Drover speeds back to his Maggy again.

O Tweed! gentle Tweed, as I pass your green vales,

More than life, more than love, my tir’d Spirit inhales;

There Scotland, my darling, lies full in my view;

With her barefooted lasses, and mountains so blue;

To the mountains away! my heart bounds like the hind;

For home is so sweet, and my Maggy so kind.

As day after day I still follow my course,

And in fancy trace back every stream to its source,

Hope cheers me up hills, where the road lies before,

O’er hills just as high, and o’er tracks of wild moor;

The keen polar star nightly rising to view;

But Maggy’s my Star, just as steady and true.

O Ghosts of my fathers! O Heroes, look down;

Fix my wandering thoughts on your deeds of renown;

For the glory of Scotland reigns warm in my breast,

And fortitude grows both from toil and from rest;

May your deeds and your worth be for ever in view,

And may Maggy bear sons not unworthy of you.

Love, why do you urge me, so weary and poor?

I cannot step faster, I cannot do more;